- July 24, 2006

- Posted by Marc

Mark Jenkins Profiled in the Washington Post

Over the weekend, the Washington Post ran a large profile on Mark Jenkins. It’s a terrific piece.

Here’s the article in its entirety:

That’s Mark Jenkins All Over

Street Artist Reproduces Himself in Tape Throughout the District

By Adriane Quinlan

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, July 23, 2006; N01

Washington is sterile. Dead. “I feel like I live in a tiny train station village.”

Local artist Mark Jenkins says that is the problem his work seeks to solve.

Like a child hunched over a make-believe town, playing tricks on tin conductors, Jenkins is laying out his own monuments over the city’s, installing sculptures on the street (without authorization) to rejuvenate what he calls “the cemetery.” He has popped red clown noses on the bronze big cats guarding the Piney Branch Bridge, floated translucent ducks in gritty gutters and popped oversized lollipop heads onto the stems of parking meters.

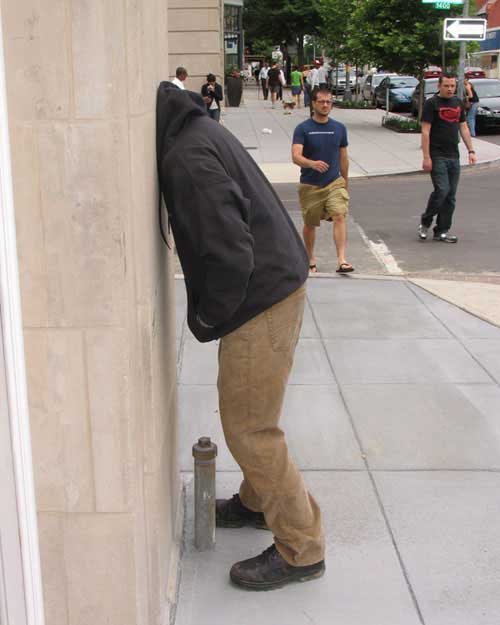

He has become best known, though, for the population of men made of tape—figurative sculptures “cast” from his own form with clear packing tape. He has positioned these “tape men” all over Washington over the past three years, a project that has gained him a measure of international fame.

Jenkins’s tape men have appeared in an art book published in Berlin (“Hidden Track: How Visual Culture Is Going Places”), a Korean news Web site ran an interview with him, and a French glossy featured a portfolio of his work. He’s popular among artists, as well: A Connecticut teenager and a grad student posted fan-mail requesting permission to work in tape; he has presented on a panel to the “Geek Graffiti” class taught in conjunction with Parsons School of Design; and two art teachers—one in Long Island, another in Kansas—led classrooms in an exercise of tape-cast self-portraits.

He has become the “first celebrity 3D street artist,” says Marc Schiller, who runs the Wooster Collective, the online hub ( http://woostercollective.com/ ) that showcases digital images of urban installations. In December, Schiller sanctioned 3D street art on his Web site as its own category, and Jenkins is the artist most featured.

“Mark’s stuff pulls you out of that zombielike experience that all of us have in the cities,” Schiller says.

Last month, when Jenkins planted three-quarters of a man, feet flailing, atop a gray utility box on the wedge of concrete between Columbia Avenue and 16th Street, the sight slowed a bus, caused cars to circle around for a second look and moved passersby to pull out camera phones. That installation was part of his latest project, “Embed,” which takes the tape men and dresses them in his own worn castoffs.

Although the thousands who have seen his tape men have literally gazed through Jenkins’s figure—medium build, about 5-foot-10—the man in the flesh is shy: “I try to keep a low profile,” Jenkins says, acting the part of just another ordinary dude in a navy polo and khakis, buying a cold can of Coke at a street stall on Independence Avenue.

“Maybe I’m not an artist,” he says, “but like an amateur psychologist doing amateur field studies using tape men as a medium.” Or, he says half-joking, “Maybe I was contacted to clone myself.”

The prototype for that cloned population was born in Fairfax and graduated from Virginia Tech with a degree in geology—“An excuse to work outside,” says Jenkins, 35, who works as a Web designer for a Washington-based nonprofit group. He left the States to hike the Andes, eventually settling in Rio de Janeiro to teach English.

In 2003, bored after a day in the classroom, he made a ball out of clear tape to toss around. It was a medium he discovered in a grade-school homeroom 20 years before, when he covered a marker in plastic wrap and tape, made an incision and removed the marker. He was so impressed by the near-perfect transparent mold that he wrapped his whole hand before the teacher could scold him for wasting.

In Rio, Jenkins was the teacher, and so he went on to wrap everything in the apartment—every pot, pan, even the toilet. His apartment started to reek of the oniony, plastic whiff of the backside of a piece of cheap tape. Was that dangerous? Better call 3M.

“They were like, ‘Yeah, it’s fine,’ and I was like, ‘What if there are six or seven hundred rolls degassing in a small flat?’ And they were like, ‘Maybe you should get a cartridge respirator.’ “

He did, and set about casting the only thing left. Starting at the feet, Jenkins mummified himself in tape (the lower back was particularly difficult) before realizing that his circulation was being cut off. That loss of feeling plus a pair of sleek new scissors became a recipe for disaster: blood all over the apartment, a pair of cut-up legs in the middle of the carpet.

Eventually, he perfected the craft.

“I’m not OCD but I have those tendencies,” he says. A clip he posted to the video Web site YouTube.com shows how he casts his own head, with a warning at the outset cautioning viewers not to imitate for fear of suffocation.

Jenkins took his first perfect reproduction and threw it into a Rio dumpster. A dewy angel of glistening tape, it drew mixed attention—some viewers were repulsed, but one man even held his son up to peer into the garbage. If Jenkins wasn’t already hooked, he was now. By throwing away what was an exact copy of himself, he experienced what he can best describe as an actual out-of-body experience. “I saw the garbage truck come by and dispose of it. It’s destruction of the self.”

It’s also a form of self-examination. Jenkins realized he could literally project himself into positions and places he otherwise would never linger. Returning to Washington in 2004, he positioned tape men as beggars on the sidewalk, stood one upside-down in a handstand on 14th Street, and cloned a fleet to wave at passing traffic from the snow banks blanketing Braddock Road.

In March, he achieved a breakthrough at Meridian Park’s statue of female “Serenity”—one Jenkins figure knelt at her feet while the other pleaded upward for some sort of acknowledgment. The tape men seemed to somehow bring the stone to life and the passersby who stopped to examine the new sculptures found themselves reexamining the white Carrara marble of “Serenity” as well, just as the tape men did. “People who look into the install become part of the install, too,” Jenkins says. “It’s kind of surreal. . . . It takes over everything.”

As good art often does, Jenkins’s work makes the ordinary appear strange.

He seeks not to confuse with a cryptic tag or impress with a traditional monument, but to engage. Whereas art in a museum is framed as art, Jenkins appreciates that passersby have to make decisions about what they find on the street. Viewers often will ask him what the tape pieces are, and whether they are “art.” “I just want them to ask that question,” he says.

In that way, Jenkins’s work breaks from most street art on the Wooster site—from graffiti to wheat-paste posters to those infamous “Obey” stickers featuring the noggin of Andre the Giant—in that it does not deface the city but is innocent and literally transparent. For that, Schiller says, “Mark is redefining uncommissioned illegal art.”

Jenkins saw online interest peak with his most approachable project, labeled “storker.” From a doll purchased in Brazil, he fathered more than 60 tape babies that seemed to pull down signs, wheel abandoned shopping carts, crawl up the feet of a begrudging commander on his oxidized iron horse. By choosing to cast a baby doll, Jenkins was toying with an impulse to protect a child from the harsh city environment.

Biking after work, Jenkins is less artist, more location scout. “The city becomes a puzzle,” he says. “My mind’s always moving like a Rubik’s cube.” Passing a “Do Not Enter” sign, he wonders, “What if I split my sculpture in half and had half entering the sign and half passing through it.” At the Lincoln Memorial, he thinks: “I’d like to cast Lincoln’s head in tape and keep it in my apartment. But there are the Park Police.”

At the Reflecting Pool, he recalls when he floated “water spiders” to skim the surface. Parking meters “cash my brain,” Jenkins says. “I was thinking the ears for a big bunny. Or shoes, a guy lying on his back with his feet up somehow.”

And when he saw the ubiquitous fiberglass pandas, he thought of making one that was “too racy—like one the city wouldn’t allow.” In March, he unveiled a prostitute panda—bear head tacked to the cast of a svelte mannequin pimped out in platform heels.

“It was still chilly and so someone put like a wool scarf around her neck that had little panda bears around it,” says Victoria Reis, executive director of Transformer Gallery, which requested that Jenkins install it on its street.

Another gallery contacted him for a commission. So Jenkins purchased $1,000 worth of tape and cast an entire Honda Civic. He wrapped it in plastic, taped over that layer by layer, cut that surface off of the car and reinforced the final, transparent automobile with glass rods. Looking at the glassy husk, one might have thought that the Civic had cast off a clear shell, like a snake that molts its skin. “I was looking for the threshold,” Jenkins says. The car wouldn’t fit into the gallery.

So much the better. To Jenkins, galleries are “aquariums,” because “all art could swim out on the street, or because art’s treated like little exotic fish that can’t survive outside.”

Turning away from a lively 3D street art community in New York, Jenkins chooses to remain a black sheep in Washington because his work wouldn’t make as much sense anywhere else. He is an environmental artist, and this is his environment—like a mash-up between typical graffiti scrawler and the urban evolution of “environmental artist” Andy Goldsworthy (whom Jenkins speaks of admirably and often).

Although Jenkins’s pieces often feel silly—parking meters as lollipops?—they are meant to satirize objects designed by the government to restrain us. “Those lollies were outside the Department of Energy,” Jenkins says. “So there was kind of a joke like: ‘Where do we get our energy from? Sugar?’ “

Says Jenkins: “D.C. is perfect because it’s the control center.”