- August 3, 2009

- Posted by Marc

Shit We’re Diggin’: The Photography of Tim Hetherington

From our friend Faith47 in Cape Town comes a link to the amazing photography of Tim Hetherington.

Hetherington, born in Liverpool, is now based in New York and shoots for Vanity Fair magazine.

He writes in a recent blog entry for the New York Times:

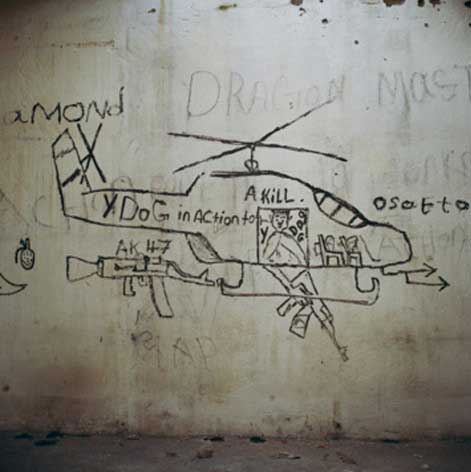

In 2000, a U.N. combat unit entered a deserted village near Shegbwema in eastern Sierra Leone — territory then held by the Revolutionary United Front, a rebel group infamous for its use of child soldiers and widespread amputations. The abandoned buildings were covered with cryptic and deranged drawings. Here and there were sentences, names, questions and statements — all of which made no sense to me at that time. Empty of life, the village was an eerie and suffocating place, and the drawings hinted at a deeper psychosis.

Three years later in neighboring Liberia, I found myself staring at similar drawings and scrawled taglines in the dilapidated frontline town of Tubmanberg, where I lived with the rebels from the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy, a ragtag army of dissidents and young men attempting to overthrow President Charles Taylor.

I started a more deliberate documentation of the graffiti that continued over the next three years. As some of the images reveal, rape and sexual abuse were common in Liberia’s violent civil war. Amnesty International estimates that between 60 and 70 percent of the population suffered some form of sexual violence during the conflict. Children became killers, schools were scenes of brutality — society itself had become inverted.

You can see more of the images on Tim’s website.

Perched on a hill above the village of Zwordemai in the northern county of Lofa stands a well-built bungalow. The house changed hands on numerous occasions over the course of the war, and was occupied by whichever faction happened to be controlling the area. Bearing more than the usual traces of war, it was obvious that the place had witnessed extreme acts of brutality. Outside, a graffiti tag on the wall stated, “This is love’s forces.” A local schoolteacher later led me into the forest behind and down into a ravine where she told me hundreds of people had been killed over the years and their bodies dumped. She described one occasion when a long line of young men had been brought past the house, walking together in crocodile formation, with their necks bound by rope.

Mr. Taylor’s fighters passed by the house on their way to the town of Foya and across the border to fight in neighboring Sierra Leone. Mr. Taylor had threatened his neighbor that it would taste the bitter fruit of war for harboring dissident rebel groups, and here in this house I found scrawled references to the Revolutionary United Front, which he currently stands accused of having armed and financed. It got me thinking again about the patrol to the abandoned village in Shegbwema where I’d first come across these traces of war.