- February 25, 2008

- Posted by Marc

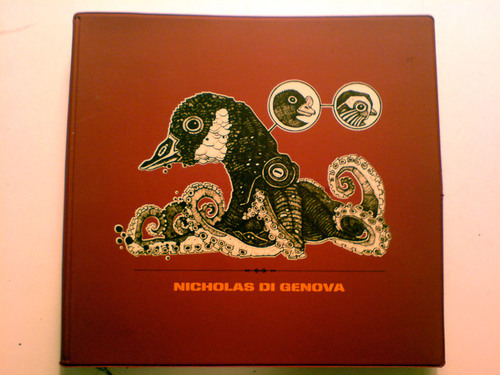

Zak Smith On Nicholas DiGenova’s Upcoming Book For Belio

“I just got my copy of Nicholas DiGenova’s new monograph in the mail. It is a fine thing—about 6’ inches square, and somehow still so much more satisfying than 90% of the oversized coffee-table books lying around this place.

When I have to explain to some visitor who doesn’t already know about some artist—“Fucking Bernini, man” or “Y’know Daido Moriyama” I pick up these huge editions and I riffle through the pages and pick out the particularly good ones and point. But I can tell already I’m not going to do that with this book. When people need to be told about DiGenova I will just toss this little book across the room (I will ruin it, I will keep having to buy more) and let it fall open to any page, because all the pages are spectacular—and there are a lot of pages, so you should buy it if you haven’t

Am I biased? True, Nick is my friend, but only because when I first saw his work, I knew I had to meet whoever made it—I knew and liked the pictures long before I knew and liked him. So no, this is not a biased book review.

I think actually reviewing art books is stupid—there’s the internet and you can just look and see for yourself, but I have a special reason here.

Here is my special reason—I need everyone to know, despite the fact that this book is the size and shape of a CD and the back of it is full of deliriously-laid out photos designed to make Nick and his works and friends and his repulsive studio in his cold corner of Toronto reeking of poultry and spraypaint seem young and fast and exciting and an introduction which mixes mad euro-rhetoric with weird translation to make gushing and weirdly oblique claims for the work that I dare anyone living to understand, that this is Art, with a capital “A”. Not just very good—but important and innovative. Know that when we are ash and our machines are rust and ruin they will dig up a great deal of what we call Contemporary Art and they will put it in the scholarly basement museums where they keep old boats and spoons and pot shards because it will look like nothing more than Information and Opinion but that when they dig up DY 005: Nicholas DiGenova people will want it and people will keep it and no mater what atrophy or evolution people have gone through in the intervening years—whether the people are starved or half-mad or half-fish-they will pay money to see it.

What is it? Almost nothing—pictures of unlikely hybrid animals. Hardly the first work on the subject. Almost meaningless. There is no philosophy to be grasped or knowledge to be gained by studying these ridiculous animals. And that is the trick—because that means that all that is going on in, say, “Bi-Necked Amphibious Climber (Piloted By Member Of The Series 7 Militia)” (2006)—and any nervous system calling itself human will have to admit that there is a lot going on—is art. Nicholas DiGenova’s pictures succeed over and over and over at reminding us that the hardest and best challenge in art is just this: making some thing that you would rather be looking at than not looking at. Look at the many different feathers, look at the many claws, look at the tender loving dots like the way ancient Australians drew kangaroos, look at the faces of things that never lived but that feel so much more like the fresh bite of life than faux-humble faux-naive humdrumming of stoner expressionists fussing about finding ways to fumblingly shuffle human features around their traditional and fudge-colored canvasses, look at the thousand ingenuities of scale and scaliness necessary to hybridize and make the monsters into pictures, look at the furniture of someone else’s mind—shorn of all the toothpaste and lightbulb-thoughts we have in common because we live on the same planet and in the same time. This is art. This the human experience, involuted and alien and accomplishing nothing but being there and being worth it.

DiGenova’s work is like comic books and it is like graffiti and everyone knows that and everyone says that, but what should be obvious and I guess from the chatter isn’t is how eagerly he takes advantage of the fact that most of what is in this book isn’t comics and isn’t graffiti and that therefore there are no deadlines or cops to chase him away from lavishing brand new forms of attention on the images his comic-book-crisp and graffiti-quick line makes possible. That is, he gives work new depth and weight and in a time when we are all perfectly aware how free and open and downloadable everything is and that every imaginable point of view is available and represented (poorly) somewhere on some nearby cable channel or website the only thing we need and don’t have is depth and weight—the feeling that a constantly contemplating sentient mind is working its way toward some new thing as hard as we are. He paints his way across an idea as useless and absurd and (by local standards) redundant as a “Siamese Six-Shooter Stork” and it somehow comes out more uncanny and haunting than any flat, dead rectangle slathered with nothing but fiction has any right to be. Nicholas DiGenova has rendered a corner of human existence more absorbing, he has put out a book that can sit on your shelf near your bed and which, when opened up, does thing like flipping on a switch in a room in your head which you didn’t know was there. This is new. This is a thing that does not look like other things. This is a gorgeous monstrous hybrid. Inasmuch as this work is like graffiti and like comics this work may be young and hip, but no more young and hip than a million things that are much worse. That’s incidental. This is not some clever crap that is there to make you feel clever even though you’re not. This is not here to prove to your friends that you know about skateboards or custom cars or Michelle Foucault or keyboardy music or even Art. This is not a bandwagon you will wish you’d jumped on. This is not a thing made to comment on some other thing because the person was scared to just say it. This isn’t here to tell you something, or make you think about something or otherwise assume it knows what’s good for you. This is a thing-in-itself. This is the product of a mind that needs to see what the things in it look like when they are in front of it because they are more complicated than what can be held inside it. These are the kinds of images that—if given the attention they deserve—will make tomorrow look different from today. And better.”.. Zak Smith